Welcome to Pushing Buttons, the Guardian’s gaming newsletter. If you’d like to receive it in your inbox every week, just pop your email in below – and check your inbox (and spam) for the confirmation email.

Sign up for Pushing Buttons, our weekly guide to what’s going on in video games.

This week marks a truly important video game anniversary: it is 50 years since Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney incorporated Atari Inc, the company that laid the foundations for the video games industry. There have been many appraisals of the company and its landmark achievements in the games press over the past few days – from the arrival of a Pong machine in Andy Capp’s Tavern in Sunnyvale, California, in 1972, through classic titles such as Breakout, Asteroids and Missile Commands, to the iconic home consoles. So many moments of creative genius, so many genres, concepts and conventions bursting into existence at the hands of scruffy engineers and designers such as Ed Logg, Larry Kaplan and Dona Bailey.

But one element that often gets overlooked in these nostalgic reveries is the way in which Atari taught the first generation of electronic gamers how to think symbolically. With two rectangles and a square, Pong invited us to visualise tennis, while Night Driver’s series of moving rectangles convinced us we were driving a car. Some will point to the 1972 console the Magnavox Odyssey as the originator of these concepts, but it was Atari putting them in arcade machines – and later consoles –all over the world.

It was also Atari that generated a whole universe around its simple games. Through beautiful cabinet designs, expert use of iconography and graphic design, and the gorgeous illustrations on its Atari VCS cartridges, the company sought to simulate the imagination of players before they even held the controller. The boxes for titles such as Berzerk and Defender, all highly abstract and visually simple games, were alive with drama; they showed human characters, explosions and colours that were impossible to achieve on screen at the time, quietly providing players with the imaginative tools they needed to become immersed. Would we have cared so much about the fate of the lifeless rock at the base of the screen in Missile Command if it hadn’t been for George Opperman’s package art? The tense commander at his desk, the explosions, the missiles seemingly scorching out of the box itself …

It was George Opperman who also designed Atari’s now legendary logo, consisting of three simple lines, the two exterior shafts curving inwards toward the peak. Over the years Opperman claimed many influences for his design – Mount Fuji, Japanese alphabet symbols, Pong itself – personally, I’ve always viewed it as a spaceship. But it’s how the image seems to sum up the excitement and futuristic promise of the company that really matters. When we see the logo flash briefly on the screen in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, it’s a quick visual signifier that this is a highly technological landscape. It fits in perfectly with a world of androids and flying cars.

Nolan Bushnell saw how video games could naturally bleed from the screen into real space, meat space. During the 1970s, the industry started in pubs and taverns, then moved into arcades and eventually the home, and they had effects on all of them: they changed behaviours and got written into our lives in subtle ways. His introduction of the Chuck E Cheese pizza restaurant chain, which combined family eating with a video game arcade, brilliantly monetised the ways that games, although graphically simple, had worked their way from the TV screen to dinner table conversation. We laugh about how the original VCS console had wood panelling, but this was a deliberate attempt to ape the aesthetics of the 1970s living room, with its wooden furniture, TV and stereo cabinets. Atari understood that assimilation would be a vital element of success.

Even now, in this age of near photorealism, video games rely on the kind of abstractions that Atari perfected. The heart symbols to denote the number of lives we have left; the heavy use of icons and exterior narratives; the endless references to familiar cinema tropes. We saw Atari being played on TV shows and films, we saw Atari in comics. While its games were still being drawn with two sprites each a single byte in size, the iconography of Atari was out there in the world. It’s something Nintendo would learn from, and later Sony, with its cultural melting pot of a console: the PlayStation. Atari was a myth maker too: from the Easter egg hidden in Adventure to the buried copies of E.T. in the California desert, the company itself became a source of digital folklore that took on meanings beyond anything portrayed on your TV.

50 years ago, Atari began to show us that games exist in a strange liminal space between the screen and the brain, and they are constantly able to escape. The dots on the screen are only ever part of the picture, and the picture never stops moving.

What to play

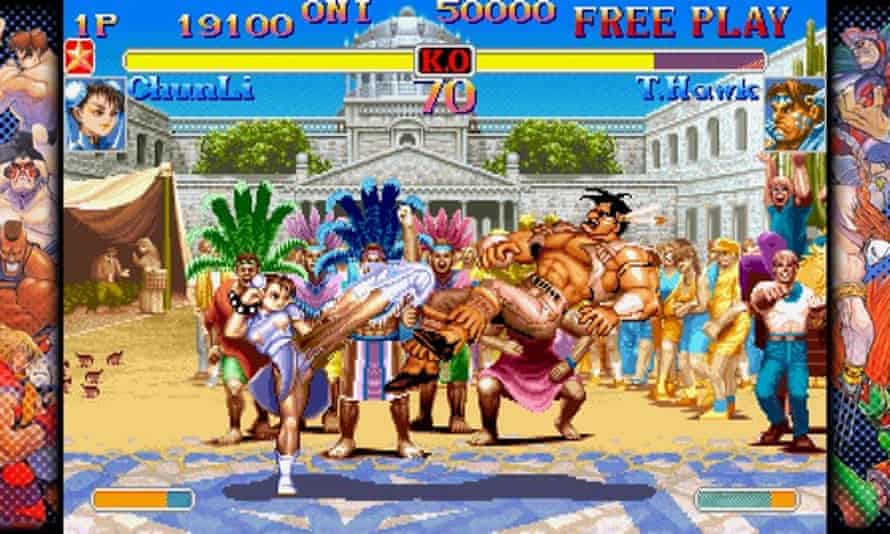

While we’re in a nostalgic mood, I’m really enjoying Capcom Fighting Collection. You’d probably expect a dozen famous titles from the Street Fighter series, but that’s already been covered by Street Fighter 30th Anniversary Collection. Instead, we get five games from the spooky, goth-infused Darkstalkers series, the mid-1990s fantasy-themed Red Earth and a bunch of offbeat Street Fighter dalliances including the ridiculously compelling Super Puzzle Fighter II Turbo, which brilliantly combined fighting game dynamics with … Tetris. The games are filled with blistering attacks and truly imaginative character designs, all lovingly updated for the modern era.

Available on: PC, PS4, Switch, Xbox One

Approximate playtime: As long as you want

What to read

-

Eurogamer is running a whole series of features for Pride, including this piece talking to Captain Fluke about being the first openly trans esports commentator and this one on the joy of gay fan faction and mods. Elsewhere, IGN has listed its favourite ever LGBT+ characters in video games.

-

Verge has a really interesting piece on a group of creatives making branded worlds for big companies in Fortnite. Everyone talks about Facebook when referencing the coming era of the metaverse, but I’m pretty sure Fortnite is going to be just as important as an explorable shared space for interconnected worlds – and the advertising potential therein.

-

We also found out this week that Hidetaka Miyazaki, the creative genius behind Dark Souls and Elden Ring, is almost finished on his next project. This is good news for me as, after 225 hours, I’m nearing the end of Elden Ring and would be very happy to slide straight into his next game if possible.

-

If I’ve got you interested in Atari’s design and illustration philosophy, The Art of Atari by Tim Lapetino is a gorgeous book. For a more technical analysis of the company, try Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System by Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost.

What to click

‘A little bit addictive and the right amount hard’: new video game is based on poems of Emily Dickinson

Cannon Arm and the Arcade Quest review – lovable gamers on mission to break record

Fire Emblem Warriors: Three Hopes review – wild battles liven up a familiar anime franchise

Melbourne startup raises $9m for mental wellness game based on tending houseplants

Question block

This week’s question comes from Tim and his daughter Caitlin, and is answered by Keza:

“We got really into Hades over lockdown, loving the ‘it’s the same each time but really different too’ concept as well as the lore and the artwork. Can you recommend a similar game that we could play together?”

Hades is what’s known as a roguelike – one of those games where you have to start again from the beginning each time, but each playthrough throws different challenges at you – and, happily for you both, this genre has been having a moment over the past few years. Hades is a contender for the very best game in this genre, so it’s hard to rival, but here are some others to try.

Dead Cells is a kind of cyberpunk-fantasy action game where you gradually explore a shapeshifting castle; Spelunky 2 has you delving down below the Earth through caves full of amusing hazards, and has a great sense of humour (you can also play co-op); Into the Breach is something a little different, a strategy game where you have to defend the world from hostile invaders, travelling back in time after each failed attempt. And for a story and art style as good as that of Hades with a different gameplay feel, try developer Supergiant’s previous games Pyre, Transistor and Bastion, if you haven’t already.